Cantor–Bernstein–Schroeder theorem

In set theory, the Cantor–Bernstein–Schroeder theorem, named after Georg Cantor, Felix Bernstein, and Ernst Schröder, states that, if there exist injective functions f : A → B and g : B → A between the sets A and B, then there exists a bijective function h : A → B. In terms of the cardinality of the two sets, this means that if |A| ≤ |B| and |B| ≤ |A|, then |A| = |B|; that is, A and B are equipollent. This is a useful feature in the ordering of cardinal numbers.

The theorem is also known as the Schroeder–Bernstein theorem, the Cantor–Bernstein theorem, or the Cantor–Schroeder–Bernstein theorem.

An important feature of this theorem is that it does not rely on the axiom of choice.

Contents |

Proof

This proof is attributed to Julius König.[1]

Assume without loss of generality that A and B are disjoint. For any a in A or b in B we can form a unique two-sided sequence of elements that are alternately in A and B, by repeatedly applying  and

and  to go right and

to go right and  and

and  to go left (where defined).

to go left (where defined).

For any particular a, this sequence may terminate to the left or not, at a point where  or

or  is not defined.

is not defined.

Call such a sequence (and all its elements) an A-stopper, if it stops at an element of A, or a B-stopper if it stops at an element of B. Otherwise, call it doubly infinite if all the elements are distinct or cyclic if it repeats.

By the fact that  and

and  are injective functions, each a in A and b in B is in exactly one such sequence to within identity, (as if an element occurs in two sequences, all elements to the left and to the right must be the same in both, by definition).

are injective functions, each a in A and b in B is in exactly one such sequence to within identity, (as if an element occurs in two sequences, all elements to the left and to the right must be the same in both, by definition).

By the above observation, the sequences form a partition of the whole of the disjoint union of A and B, hence it suffices to produce a bijection between the elements of A and B in each of the sequences separately.

For an A-stopper, the function  is a bijection between its elements in A and its elements in B.

is a bijection between its elements in A and its elements in B.

For a B-stopper, the function  is a bijection between its elements in B and its elements in A.

is a bijection between its elements in B and its elements in A.

For a doubly infinite sequence or a cyclic sequence, either  or

or  will do.

will do.

In the alternate proof,  can be interpreted as the set of n-th elements of A-stoppers (starting from 0).

can be interpreted as the set of n-th elements of A-stoppers (starting from 0).

Indeed,  is the set of elements for which

is the set of elements for which  is not defined, which is the set of starting elements of A-stoppers,

is not defined, which is the set of starting elements of A-stoppers,  is the set of elements for which

is the set of elements for which  is defined but

is defined but  is not, i.e. the set of second elements of A-stoppers, and so on.

is not, i.e. the set of second elements of A-stoppers, and so on.

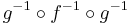

The bijection  is defined as

is defined as  on

on  and

and  everywhere else, which means

everywhere else, which means  on A-stoppers and

on A-stoppers and  everywhere else, consistently with the proof below.

everywhere else, consistently with the proof below.

Visualization

The definition of h can be visualized with the following diagram.

Displayed are parts of the (disjoint) sets A and B together with parts of the mappings f and g. If the set A ∪ B, together with the two maps, is interpreted as a directed graph, then this bipartite graph has several connected components.

These can be divided into four types: paths extending infinitely to both directions, finite cycles of even length, infinite paths starting in the set A, and infinite paths starting in the set B (the path passing through the element a in the diagram is infinite in both directions, so the diagram contains one path of every type). In general, it is not possible to decide in a finite number of steps which type of path a given element of A or B belongs to.

The set C defined above contains precisely the elements of A which are part of an infinite path starting in A. The map h is then defined in such a way that for every path it yields a bijection that maps each element of A in the path to an element of B directly before or after it in the path. For the path that is infinite in both directions, and for the finite cycles, we choose to map every element to its predecessor in the path.

Alternate proof

Below follows an alternate proof.

Idea of the proof: Redefine f in certain points to make it surjective. At first, redefine it on the image of g for it to be the inverse function of g. However, this might destroy injectivity, so correct this problem iteratively, by making the amount of points redefined smaller, up to a minimum possible, shifting the problem "to infinity" and therefore out of sight.

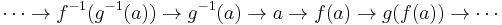

More precisely, this means to leave f unchanged initially on C0 := A \ g[B]. However, then every element of f[C0] has two preimages, one under f and one under g –1. Therefore, leave f unchanged on the union of C0 and C1 := g[f[C0]]. However, then every element of f[C1] has two preimages, correct this by leaving f unchanged on the union of C0, C1, and C2 := g[f[C1]] and so on. Leaving f unchanged on the countable union C of C0 and all these Cn+1 = g[f[Cn]] solves the problem, because g[f[C]] is a subset of C and no additional union is necessary.

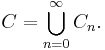

Proof: Define

and

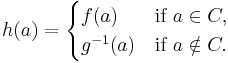

Then, for every a ∈ A define

If a is not in C, then, in particular, a is not in C0. Hence a ∈ g[B] by the definition of C0. Since g is injective, its preimage g –1(a) is therefore well defined.

It remains to check the following properties of the map h : A → B to verify that it is the desired bijection:

- Surjectivity: Consider any b ∈ B. If b ∈ f[C], then there is an a ∈ C with b = f(a). Hence b = h(a) by the definition of h. If b is not in f[C], define a = g(b). By definition of C0, this a cannot be in C0. Since f[Cn] is a subset of f[C], it follows that b is not in any f[Cn], hence a = g(b) is not in any Cn+1 = g[f[Cn]] by the recursive definition of these sets. Therefore, a is not in C. Then b = g –1(a) = h(a) by the definition of h.

- Injectivity: Since f is injective on A, which comprises C, and g –1 is injective on g[B], which comprises the complement of C, it suffices to show that the assumption f(c) = g –1(a) for c ∈ C and a ∈ A \ C leads to a contradiction (this means the original problem, the lack of injectivity mentioned in the idea of the proof above, is solved by the clever definition of h). Since c ∈ C, there exists an integer n ≥ 0 such that c ∈ Cn. Hence g(f(c)) is in Cn+1 and therefore in C, too. However, g(f(c)) = g(g –1(a)) = a is not in C — contradiction.

Note that the above definition of h is nonconstructive, in the sense that there exists no general method to decide in a finite number of steps, for any given sets A and B and injections f and g, whether an element a of A does not lie in C. For special sets and maps this might, of course, be possible.

Original proof

An earlier proof by Cantor relied, in effect, on the axiom of choice by inferring the result as a corollary of the well-ordering theorem. The argument given above shows that the result can be proved without using the axiom of choice.

Furthermore, there is a simple proof which uses Tarski's fixed point theorem.[2]

History

As it is often the case in mathematics, the name of this theorem does not truly reflect its history. The traditional name "Schröder-Bernstein" is based on two proofs published independently in 1898. Cantor is often added because he first stated the theorem in 1895, while Schröder's name is often omitted because his proof turned out to be flawed while the name of the mathematician who first proved it is not connected with the theorem.

In reality, the history was more complicated:

- 1887 Richard Dedekind proves the theorem but does not publish it.

- 1895 Georg Cantor states the theorem in his first paper on set theory and transfinite numbers (as an easy consequence of the linear order of cardinal numbers which he was going to prove later).

- 1896 Ernst Schröder announces a proof (as a corollary of a more general statement).

- 1897 Felix Bernstein, a young student in Cantor's Seminar, presents his proof.

- 1897 After a visit by Bernstein, Dedekind independently proves it a second time.

- 1898 Bernstein's proof is published by Émile Borel in his book on functions. (Communicated by Cantor at the 1897 congress in Zürich.)

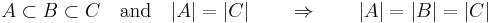

Both proofs of Dedekind are based on his famous memoir Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen? and derive it as a corollary of a proposition equivalent to statement C in Cantor's paper:

Cantor observed this property as early as 1882/83 during his studies in set theory and transfinite numbers and therefore (implicitly) relying on the Axiom of Choice.

See also

- Schröder–Bernstein theorem for measurable spaces

- Schröder–Bernstein theorems for operator algebras

- Schröder–Bernstein property

Notes

- ^ J. König (1906). "Sur la théorie des ensembles". Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences 143: 110–112. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k30977.image.f110.langEN.

- ^ R. Uhl, "Tarski's Fixed Point Theorem", from MathWorld–a Wolfram Web Resource, created by Eric W. Weisstein. (Example 3)

References

This article incorporates material from the Citizendium article "Schröder-Bernstein_theorem", which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License but not under the GFDL. Peter Schmitt contributed the History section to Citizendium which TakuyaMurata copied into this article.

- Proofs from THE BOOK, p. 90. ISBN 3540404600

- Proof of the Bernstein–Schroeder theorem on PlanetMath

- MathPath – Explanation of and remarks on the proof of Cantor–Bernstein Theorem

- Papers on the history of the Cantor–Bernstein theorem

External links

- Citizendium: Schröder-Bernstein theorem and Schröder–Bernstein property

![C_0=A\setminus g[B],\qquad C_{n%2B1}=g[f[C_n]]\quad \mbox{ for all }n\ge 0,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6ed7e04b029de2934545ce83f4e330c2.png)